Share Sleuth: Why cash flow is better than profits

30th November 2016 11:59

We all know a sudden rush to the head can make us look foolish. In the stockmarket, wagering large amounts of money on shares with very uncertain prospects may not only embarrass but also impoverish us.

Last month, I introduced the first of five criteria that combine to make a simple algorithm, a decision-making process, that tells me whether an investment is sensible or foolish. Some of the criteria use financial statistics. Others are more fuzzy, like the first: "How well do I understand the business?"

I give each criterion a score from zero to two, so the total score for a share will be between zero and 10. Typically, I consider shares with scores of seven or more worthy of investment, and shares with scores of five or less unworthy.

You cannot judge something you don't understand, so the first criterion is the starting point. The second is:

Does the firm generate excess returns?

If you tell me you earned £100 interest from savings in a particular account last year, I can't work out whether it was a good savings account and you received a high rate of interest, or whether you just had a lot of money in the account.

Likewise, a company's level of profit, £100 million, say, doesn't tell me whether it is a good company.

In both cases we need to know how much was invested to make the profit. At current interest rates, the savings account might be considered good even if it took a £10,000 deposit to earn the interest.

However, a £10 billion investment to earn £100 million profit (the same return, 1% annually) would be unacceptable for a company.

Why would a business take all the risk of renting premises, employing people, buying equipment, entering contracts, and holding stock, when it could put the money in a bank and earn the same return? To justify being in business, it must earn substantially more, which is what I mean by excess return.

The return the company makes on its investment, or capital, is a measure of profitability. For a long time I've used an 8% return on capital as sufficient to justify being in business.

I might forgive one bad year in 10, say, as long as the company was still generating cash, and I would prefer a business to earn more than 8% most years.

Profit is determined by accountants, but it's dangerous to assume a profitable company is a good one. Occasionally, companies are outright frauds.

Outstanding returns needed

More often profits are, for example, inflated by rules that allow accountants to defer costs to match revenues that should be earned in the future. If the revenues don't materialise, the company will have overstated profit.

To validate profitability, we can examine how much money has entered or left the firm's bank accounts - its cash flow.

I'll rarely give a share a score of two unless cash flow is relentlessly positive and average cash flow over many years is a high proportion of average profit (80% or more).

The past, as every investor should know, is no guarantee of the future. Knowing a company has been profitable isn't the same as knowing it will be.

That's where my final three criteria come into play, and I'll reveal them in coming months.

One company instantly comes to mind for its outstanding returns over many years. It's , which makes vinyl flooring: the kind you tread on every day in hospitals, schools and offices.

I calculate average return on capital over the past 11 years has been almost 40%. It's never fallen below 34%.

James Halstead has on average earned 90% of profit in cash terms, and no less than 60% in the past 11 years.

How does the manufacturer of a mundane product earn such impressive returns? I've tried to unravel the Halstead conundrum before.

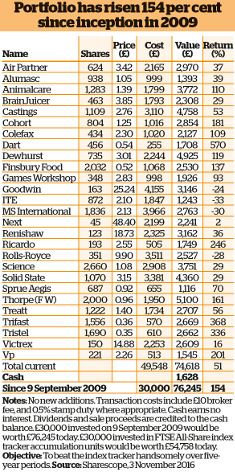

Portfolio members , and have published annual reports recently.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer. Click here to subscribe.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.

Editor's Picks