Why value investors are poised to prosper

15th December 2016 09:00

Interactive Investor is 21 years old. To celebrate, our top journalists and the great and the good of the City have written a series of articles discussing what the future might hold for investors. Here's Richard Beddard on the trials and rewards of value investing.

Life without the internet may be difficult to imagine, but few of us had heard of it when Margaret Thatcher stood down as prime minister in November 1990. In 1998, the first year in which the Office for National Statistics collected internet uptake data, less than 10% of households had internet access - yet the internet's development would combine with economic and financial deregulation that had started in the Thatcher and Reagan years, to top off the mother of all bull markets in the year 2000.

Those were glorious years for stockmarket speculators. Punctuations such as Black Monday in 1987 and the Asian financial crisis in 1997 were severe, but normal service soon resumed, and it was widely believed that the stockmarket was a one-way street.

At the market's peak, took over Mannesmann to form Europe's largest company, and an internet startup, AOL, took over one of the world's most respected publishing houses, .

A Channel 4 game show, Show Me the Money, brought the excitement of virtual trading to a daytime TV audience, and private investors met on the internet and in person to cheer their gains. Often it didn't matter what a company did, so long as its share price was rising.

Vanishing value

It was a dismal period for value investors, however. A corollary of remorselessly rising prices is that nothing looks cheap.

In the US Warren Buffett, often acclaimed as the world's greatest investor, was criticised as the performance of his investment company lagged the stockmarket average in 1999.

In the UK fund manager Tony Dye had been warning since 1996 that the market was overvalued, earning the nickname Dr Doom.

He withdrew money from shares while prices continued to climb, and the company he worked for, Phillips and Drew, lost more clients than any other fund manager. In March 2000, Dye took early retirement. Within a month, the rout had started.

The market was categorically overvalued between 1996 and 2000Had it been possible to buy a share in the FTSE All-Share index in 1980, it would have appreciated by 1,000% over the next two decades. Sixteen years into the subsequent two decades and, with the market perhaps 20% above its 2000 peak, a similar outcome appears preposterously unlikely.

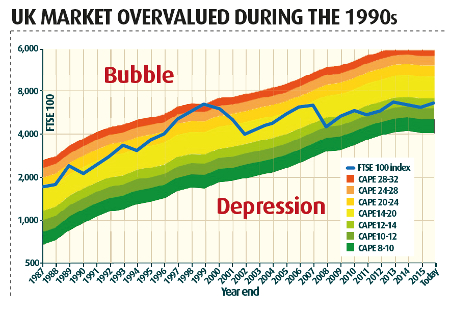

The story is etched into this chart showing the cyclically adjusted price earnings (CAPE) ratio. The chart compares the price of the index to the average of 10 years' earnings for all the companies in it, adjusted for inflation.

Chart: UK Value Investor

In hindsight, Dye was right. The market was categorically overvalued between 1996 and 2000, but since then it has flirted with a high valuation briefly and unconvincingly only once, just before the credit crunch in 2007.

Intrinsic worth

When people talk about value investing, they mean paying less for an investment than it is truly worth, its intrinsic value. Academics and investment professionals agree that the intrinsic value of an investment is the value of all the cash flows (dividends, for example) investors will receive from it in today's money.

That it is impossible, at least in most cases, to estimate future cash flows or the appropriate discount factor with any certainty doesn't stop some analysts trying. Others default to simple but very imprecise measures such as the price/earnings (PE) ratio.

Benjamin Graham is often hailed as the 'father of value investing'At the height of the dotcom boom, Vodafone shares were trading at 90 times annual earnings. Today, perceptions have changed, and it has traded on a PE of about 10 in recent years. The idea that prices can diverge a long way from intrinsic value has profited investors for generations.

Benjamin Graham, hailed as the father of value investing, likened the stockmarket to a hyperactive business partner, Mr Market, who would one day offer to buy all your shares and another day try to sell you all his. The trick, Graham said, is to hold fast until he makes you a really silly offer.

Quantitative approach

Graham died 40 years ago, but over the past two decades, academia has slowly been catching up. Psychologists and behavioural economists have publicised theories explaining why the bulk of investors overreact to events, pushing prices to extremes and giving wiser heads the opportunity to profit.

Finance professors have established funds to exploit their research, often targeting the factors value investors have always followed: price, profitability and size (smaller companies tend to perform better than larger ones), for example.

Professors aren't the only ones jumping on the quantitative bandwagon. In 2005 Joel Greenblatt, a wildly successful value fund manager, published a bestselling book that might have brought quantitative value investing to the masses.

The Little Book That Beats the Market showed how to invest systematically in good companies at cheap prices. Its associated free website told investors which stocks to invest in.

Though the book was a bestseller, it's unlikely Greenblatt has created a generation of value investors. He predicted he wouldn't.

The psychological pain of being apart from the herd means value investors are a minorityHe denied that his system would make undervalued shares so popular that they would no longer be undervalued, because over months and sometimes years his system can do worse than the stockmarket average.

Imagine throwing bad money after good, perhaps for years. Most people lose faith. Funds like those operated by Terry Smith's Fundsmith, which launched its in 2010, own shares at much higher PE ratios and still claim not to pay too much.

A company with a PE of 20 or even 40 can be good value if it is such a strong competitor that it will reinvest its profits, compounding them for a very long time.

Even discounted back to today's money, the future cash flows of such companies are reckoned to be enormous.

Old-school value investors baulk at such valuations. In a recent interview, Nick Kirrage, a fund manager at Schroders, said that buying - the kind of business Smith favours in his portfolio - on a PE of 25 is "a complete bastardisation of everything that Benjamin Graham conceived".

Twenty-one years after Interactive Investor was born, we can perhaps say three things about value investing: the zeitgeist and the CAPE chart tell us that now is probably a better time to be a value investor; value investors will disagree about where best to find value; and the psychological pain of standing apart from the herd means value investing will remain a preoccupation for only a committed - but prosperous - minority.

This article was first published in our special publication 21: Twenty-one years of Interactive Investor. Download your digital copy for free here.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.

Editor's Picks