How currency movements can wreak havoc with your ISA portfolio

31st March 2017 11:19

No matter what your feelings are about the UK's vote last June to leave the EU, if you've invested in the stockmarket, there's a good chance the Brexit vote result has increased your wealth.

The sterling sell-off since the referendum - the pound is down 20 and 10% against the dollar and euro respectively - has had dramatic consequences.

One effect has been the swelling of the coffers of large UK companies that earn substantial revenues in international markets, since overseas sales are now worth more when converted into pounds.

This is why the firms in the index of blue-chip stocks have delivered almost twice the returns achieved by FTSE 250 index companies - which typically earn more of their money in the UK - since the referendum.

Currency risk

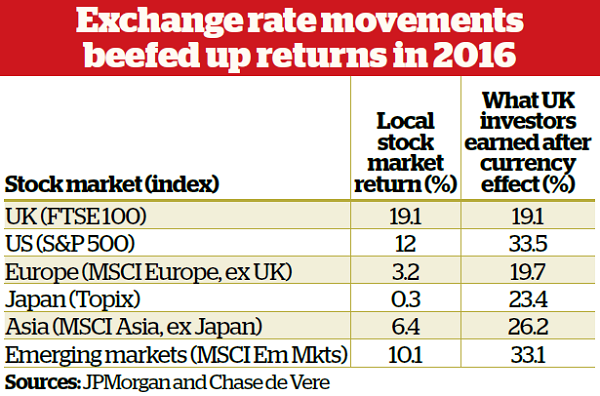

However, investors with exposure to overseas stockmarkets have benefited most from the pound's decline, as data from JPMorgan shows. The US stockmarket delivered a return of 12% last year, but for UK investors, this was worth more than 33% after conversion into sterling.

In Europe the pound's decline effectively boosted UK investors' returns from 3% to almost 20%, while returns from Japanese equities were lifted from near zero to 23%.

However, while it's natural to celebrate those gains, it's important to learn a vital lesson from what happened during 2016.

"Investors need to be aware of the potential effects of currency [exchange rates], as they can have a significant impact on their overall returns," says Patrick Connolly, a chartered financial planner at independent financial adviser Chase de Vere.

"While the effect last year was positive, there will be times when the reverse is true."

Shocks such as the Brexit vote and the extreme exchange rate movements that followed are unusual, but they remain an ever-present risk. As recently as 2015, for example, the Swiss franc rose by 30% against the euro in a single day after the Swiss central bank changed a key policy.

How to mitigate currency risks

Generally, currency volatility appears to be on the increase. For a long period following the financial crisis, the fortunes of developed economies were roughly in sync, with central banks in the US, Europe and Asia all adopting similarly loose approaches to monetary policy in an attempt to bolster growth.

More recently, however, that synchronicity has broken down. The US is now moving towards tighter policy, having already made one interest rate increase recently, while the UK economy is outperforming.

Europe and Japan, meanwhile, remain mired in gloom. One effect of this divergence has been increasing currency flows in the global economy and therefore greater exchange rate volatility.

All this begs an obvious question: what can investors do to mitigate the risks posed by currency fluctuations?

The conventional wisdom that investors should have exposure to a diversified portfolio of international equities, rather than bet the house on the UK market, is all very well, but that leaves them vulnerable to increasing exchange rate volatility.

Last year's currency gains might well be followed by losses this year if some of the Brexit uncertainties begin to resolve themselves and this supports the pound.

"If sterling strengthens significantly against the dollar again, it will have a negative effect on company profits and fund performance," warns Darius McDermott, managing director at financial adviser Chelsea Financial Services.

Assuming your overseas investments are held via collective funds, you have two options for mitigating currency risk. The first is to devolve responsibility to a fund manager.

Some funds allow managers to hedge currency exposure - in which case you'll be dependent on the manager making the right choices - but others explicitly rule this out.

Hedging currency risk

Alternatively, you can invest with one of the increasing number of international funds that offer a separate share class to investors seeking to hedge currency risk.

You'll get exposure to the same underlying assets as investors in the fund holding unhedged shares, but you'll also benefit from derivatives contracts that seek to partially or fully cancel out the effect of exchange rate movements.

Some investors appreciate hedging in this way - you get a purer exposure to the stockmarket in question - but it's not without problems. Hedged shares carry higher fees to reflect the cost of the derivatives contracts.

In addition, currency markets are notoriously difficult to call, and while a hedged position will protect you when rates move against you, you'll miss out when they move with you.

Last year that latter scenario would have proved very costly. The fund isn't trying to call the market here. The hedge simply aims to cut out currency exposure, good or bad.

"It is always dangerous to start playing with currency investments, as you're effectively just adding to the already considerable risk in equity and fixed-interest markets," warns Philippa Gee, managing director at Philippa Gee Wealth Management.

"And we're only at the start of the Brexit/Trump journey, so I would be very wary about increasing risk further."

It's worth thinking about currency movements in a broader context and the effect they might have on a stockmarket, but the jury is out on whether there is a link between the two.

Several academic studies have concluded that there is little or no correlation between the performance of a country's stockmarket and its currency's exchange rate, especially over the long term. However, some investors are convinced there is, particularly over the short term.

"A balanced view would be that a strong currency usually indicates a strong economy and vice versa," says McDermott. "But the relationship isn't really that straightforward. stockmarkets can move in different directions before or after economic moves."

Regional differences

In countries where exports account for a good chunk of the economy, a less highly valued currency provides a boost, as companies' goods and services are more competitively priced for overseas buyers.

In export-dependent countries such as Japan, a fall in the value of the currency is therefore often seen as likely to boost stockmarket valuations. The same is true in the US.

In other countries, the relationship works differently. Developing economies tend to have high levels of public and private sector debt, typically priced in dollars.

So when the value of a developing country's currency falls, the cost of servicing that debt increases, which hampers economic activity. Emerging market currency gains are therefore more likely to be associated with stronger stockmarket performance.

Over time, however, the relationship between currency and stockmarket movements may often be self-correcting.

Where a currency fall supports stockmarket outperformance, for example, flows of money into that market from global investors attracted by rising returns will eventually begin to support the exchange rate.

Equally, the natural process of investors rebalancing their portfolios after a strong run of performance from a particular market will trigger currency sales.

For these reasons, Patrick Connolly argues that an investor's best bet may be to manage their exposure to exchange rates rather than try to second guess the market.

He says: "The most sensible way to reduce these risks is to hold assets denominated in sterling and avoid over-exposure to assets in any one particular currency."

Sterling's slide positive for dividends

Just a year ago the prospects for investors hoping for generous dividends from their shareholdings looked dismal.

With energy firms struggling to maintain payouts in the face of moribund prices, financial services companies under the cosh in a low-interest rate market place and retailers facing fierce competition, most analysts forecast that dividends would fall in 2016.

However, such predictions proved wide of the mark. The total value of dividends paid by UK companies reached £84.7 billion last year, according to Capita, up 6.6% on 2015 and the second-strongest year ever recorded.

Much of the gain came courtesy of the fall in the value of the pound. Of the £5.2 billion headline increase in dividends last year, £4.8 billion was due to sterling weakness, Capita calculates.

Investors often get a double lift from a falling exchange rate when it comes to dividends. First, once companies' overseas sales are converted into pounds, they have more cash available to distribute to shareholders.

But in addition, many larger companies - including 40 members of the FTSE 100 index - pay their dividends in US dollars. So once investors exchange their payouts for sterling, they're better off.

Capita expects these virtuous effects to continue this year. "We expect 2017 dividends to [deliver] a healthy increase of 7.5%, with two-thirds of this down to the effect of the weaker pound," it forecasts.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Editor's Picks