How to profit in the new era of anti-globalisation

5th June 2017 12:26

by David Prosser from interactive investor

Share on

When social historians update the textbooks, Baden-Baden may claim a prominent place. The small German spa town would not have been the first to spring to mind for those predicting where a seismic shift in geopolitics and macroeconomics might occur, but it was here, in March, that the finance ministers of the world's biggest economies agreed the most significant change of direction in a generation - the G20's decision to drop its vow "to resist all forms of protectionism".

For many analysts, the Baden-Baden meeting marked a decisive victory for opponents of globalisation, the seemingly inexorable wave of international economic integration, free trade and political and cultural alignment that has dominated since the end of the second world war - and particularly since the end of the cold war.

America first

The immediate prompt for the G20 shift was the influence of the US - now under the presidency of Donald Trump, whose "America First" protectionist instincts are utterly at odds with the traditional US role as standard-bearer for global capitalism. However, the Trump presidency is a symptom of the fall from grace of globalisation, rather than a cause - and one of many such symptoms now in evidence all around the world.

Consider, for example, the UK's decision to vote to leave the European Union, a triumph for those who believe this country will be better off by standing alone. Look too at mounting opposition in the eurozone to integration and immigration (movement of labour is an important principle of globalisation), as seen in Italy's decision to reject constitutional reforms in last year's referendum and the significant (though ultimately minority) support for Marine Le Pen's Front National in France's recent presidential elections. In Asia, meanwhile, countries such as Sri Lanka warn that opposition to free trade is growing.

Even at Davos, where the World Economic Forum meeting might be seen as the annual general meeting of globalisation, there is recognition of the winds of change. "We may be at a point where globalisation is ending and where provincialism and nationalism are taking hold," says Ray Dalio, the founder of investment company Bridgewater Associates, one of several delegates at this year's WEF meeting to sound the alarm.

Michael Witt, affiliate professor of strategy and international business at the business school Insead, says the backlash against globalisation reflects mounting frustration with the way the spoils of economic liberalism have been shared out. "The problem is that while globalisation tends to increase overall wealth - the pie gets bigger - not everyone gains equally, and some actually lose," Witt argues. "The angry US blue-collar workers plumping for Trump, and the rural anti-EU voters in Britain, for instance, see globalisation as a project that benefits the elites at their expense."

These protestors have got a point. In many western countries, the gap between rich and poor has never been wider. Equally, while most people will welcome the news that workers in developing economies all over Asia are slowly but surely emerging from desperate poverty, those struggling to find employment or maintain their wealth in the rust belt of the US - or manufacturing towns across England and Wales, say - will naturally feel less of a warm glow.

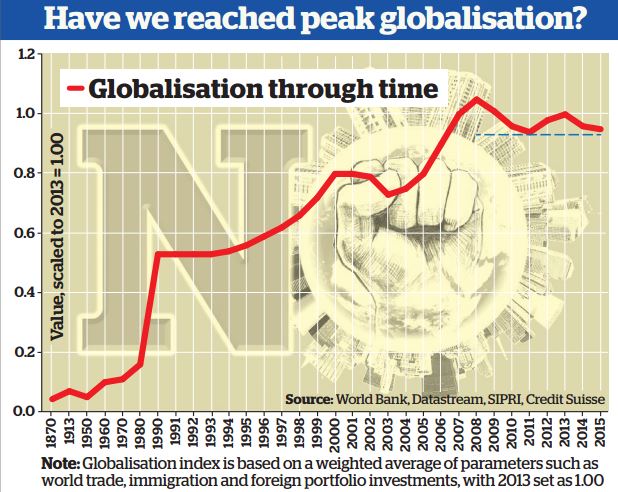

In fact, the backlash at the ballot box against globalisation is just the most visible sign of a shift that has been taking place for some time. A study published earlier this year suggests globalisation has now been ebbing for the best part of five years; as the chart below shows, its globalisation index, based on flows of trade, finance, services and people, now stands at a level not seen since the financial crisis.

Global trade as a proportion of the value of the world economy has fallen back from its peak in 2008, as Credit Suisse points out and the second chart overpage reveals.

No big trade deals since 2001

Such data reflects the underlying politics. No significant international trade agreement has been signed since the Doha trade round in 2001 passed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The prospective Trans-Pacific Partnership between the US, Japan and other Asian countries, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the US and the EU both now look fatally wounded. Even the North American Free Trade Agreement, signed more than 20 years ago, is under threat from the Trump administration.

Michael O'Sullivan, chief investment officer of Credit Suisse's international wealth division - and one of the authors of its recent study - thinks we are now at a turning point that has huge implications. "2016 may go down in history as the portentous period when globalisation as we have come to know it came to an end," he argues. "The current period effectively dates from the fall of communism and to a large extent has been driven by US multinationals, the advent of the euro, the growth of financial markets and the development of many emerging economies; if globalisation slows or changes, the consequences for companies, markets and politics will be enormous."

There are three possibilities, Credit Suisse now believes. First, globalisation may still get a second wind, particularly if governments are swift to respond to their populations' anger. As Michael Witt of Insead puts it: "There is a remedy [to such anger] - redistribution of part of the spoils of globalisation to turn the losers into winners."

The opposing - and scarily dark - scenario is that globalisation now moves from decline to outright collapse, with a sharp correction in global growth, rising protectionism, and geopolitical clashes between world powers that could easily slide into military confrontations. The third possibility is that globalisation as we know it does indeed come to an end, but that it is replaced by a more regionalised world order. What Credit Suisse dubs 'multi-polarity' is the option it is betting on as most likely.

"This scenario is based on the rise of Asia and a stabilisation of the eurozone so that the world economy rests, broadly speaking, on three pillars - the Americas, Europe and Asia, led by China," adds O'Sullivan. It would mean the rule of law, financial markets, immigration all become more regional, with corporate champions in each polarity supplanting today's dominant global multinationals.

But what would an end to globalisation mean for investors? Well, however that end plays out, there would be significant implications for the type of companies that sit at the core of many investors' portfolios.

After all, these in many cases are heavily weighted towards large, multinational businesses - either through index trackers or via active funds with significant holdings in blue-chip equities - which are precisely the companies that have most to lose from an end to ever-greater globalisation.

Christopher Lees, a senior fund manager at JO Hambro Capital Management, puts it this way. "For the past 15 years, it's been about investing in the winners of globalisation, but that's probably changing - we may have seen peak globalisation."

Scenario two from Credit Suisse, in which the era of globalisation comes crashing down suddenly, would be calamitous, with an outbreak of potentially ruinous trade wars as protectionist governments tear up free-trade agreements and move into an arms race on tariffs and trade barriers. In such circumstances, there could be some day-to-day winners, but there would also be many losers and an unnerving spike in volatility.

No winners in trade wars

To give one isolated example, in 2009, when the supposedly free-trade Obama administration got into a dispute with China and imposed tariffs on tyre imports from that country's manufacturers, shares in and , the two giants of the US domestic tyre industry, soared. But at the same time, the country's chicken producers lost $1 billion in sales as the Chinese retaliated by putting tariffs on chicken parts, and shares in those companies fell sharply. US retailers lost out too - a study by the Peterson Institute of International Economics found that in the absence of competition from China, US tyre manufactures raised prices, so both their products and Chinese tyres became more expensive, and that hit US consumers' disposable incomes to the tune of $1.1 billion (£850 million).

In fact, this episode offers an important lesson about the potential pitfalls for protectionist governments that are tempted to succumb to popular opinion. President Obama claimed his tariffs saved 1,200 jobs in the US tyre industry, but Peterson's analysis pointed out that the $1.1 billion of lost retail sales translated into 3,731 jobs lost in that industry.

For investors, meanwhile, the lesson is that agility will be required in the event of trade wars breaking out. It was easy to see those tyre company share price spikes coming, but less so to predict how China would respond and where investors would lose out - let alone to anticipate the retail setbacks in advance.

That is the nature of conflict - the actions of the other side are always difficult to anticipate and plan for. In a trade war, governments will retaliate to aggression in unexpected ways; investors won't always know which industries are to be targeted until the last moment. Moreover, every company with a global supply chain - that's more or less all large multinationals - will face rising costs.

The standard response to these sorts of pressures is to shift into defensive stocks: manufacturers of food and other consumer staples are often seen as the place to be during an economic slowdown or recession, which trade wars would undoubtedly prompt. Yet such businesses often rely on imported raw materials or overseas production - they may not be so safe either. More domestic industries, such as utilities and healthcare, might be a better bet in such circumstances. The good news is that many analysts agree with Credit Suisse's contention that a more gradual shift into regional strength is the most likely narrative from here on. "Thus far, it seems some of the more aggressive tone Trump struck on tariffs has moderated, and following his meeting with China's President Xi he appears to be more interested in tying US-Chinese trade relationships to cooperation on addressing North Korea's nuclear programme," argues Jason Hollands, managing director of wealth management firm Tilney Bestinvest.

Slow retreat ahead?

Still, a slower move away from globalisation would nonetheless prompt many of the same effects as a sudden shock, albeit over a longer period; if the end of globalisation is characterised by an insidious retreat from trade liberalisation and international co-operation, so the problems for large multinationals dependent on such values will slowly add up - technology companies, for example, might lose out from weakened international intellectual property protections, while manufacturers would see a steady decline in margins as costs increased. Such headwinds might be long-term, but investors would feel the chill nonetheless.

All of which adds up to the same message: the different scenarios in which globalisation goes into reverse all spell bad news for those large internationally connected companies that form such a large part of so many investors' portfolios. More domestically focused businesses, by contrast, have much less to lose and should therefore move into favour. Since those companies are often smaller, it makes sense to assume we'll see smaller company stocks outperform in such circumstances.

Repositioning your portfolio for a decline in globalisation

Leading investment analysts suggest moving out of funds dominated by large-cap multinational stocks if you buy the theory that the era of globalisation is drawing to a close.

"Given that anti-globalisation is likely to be better for smaller, domestically focused companies, I would suggest the ," says Adrian Lowcock, the investment director of Architas. "This is a US small and mid-cap fund managed by a very experienced and well-resourced investment team led by veteran investor Jenny Jones, who believes avoiding losses is essential for growing capital over the long term."

Mark Dampier, research director at Hargreaves Lansdown, takes a similar view. "I think it's always dangerous to invest in trends, as they have a habit of changing, but I don't think it would do investors any harm to look at smaller companies both domestically and globally," he says. "If globalisation is ending, domestic smaller companies will be the strongest beneficiary as they will market to their home countries. In that case, buying should be a good investment, or, thinking closer to home, try , or the new ."

At Philippa Gee Wealth Management, meanwhile, Philippa Gee says: "I like on the active side, and also for a UK slant. Some trust shares currently offer significant discounts - for one."

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.