Is this the beginning of the end for Google's monopoly?

16th August 2017 09:22

by Emil Ahmad from interactive investor

Share on

Since first came to the forefront of the public's conscience with its IPO in 2004, the company has been used to setting precedents for the right reasons. The tech giant's dominance in the search engine and browser space provided the perfect platform for an assault on the emerging smartphone market.

As Google basked in the glory of being the world's largest company in early 2016, the only credible challenge to its Android mobile operating system was iOS. This duopoly leads to an interesting dichotomy; it is both impressive and terrifying that Android and iOS accounted for 99.6% of global smartphone sales in the fourth quarter of 2016.

An interesting footnote to these statistics from technology researcher Gartner was fall from grace. The former market leader's measly 207,000 sales represented a market share of 0.0%.

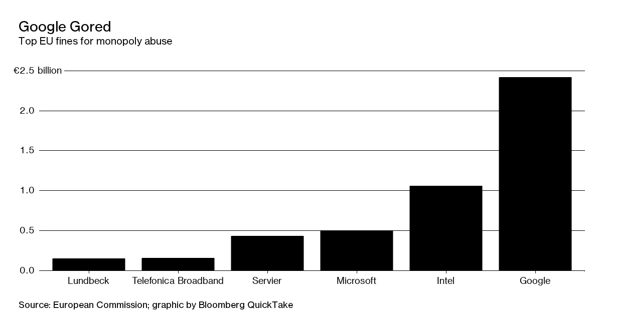

As Google faces the unwelcome precedent of a record €2.4 billion (£1.86 billion) EU Antitrust fine, it would be advised to take heed of BlackBerry's demise. Dominance may not last forever and, as history has taught us, monopolies can be broken.

The seven-year itch

This record antitrust fine was seven years in the making, with initial investigations commencing in February 2010. In essence, the EU has decided that the company has abused its position as the world's dominant search engine to the detriment of smaller shopping search competitors.

Google began promoting its online comparison-shopping function in 2008. This service has been favoured to such an extent that rival comparison sites only started to make an appearance on the lowly depths of page four.

As the first page typically accounts for 95% of all clicks, it would not be an exaggeration to suggest that Google's rivals were competing for crumbs rather than just a smaller slice of the pie.

For a company with a $90 billion cash pot, it would be easy to dismiss this fine as a drop in the ocean and for business to simply continue as usual. However, the nature of this ruling has far wider ramifications for Google and the tech sector as a whole.

This binding order from the EU states that Google must "stop its illegal conduct" and treat its rivals in an equitable manner. Over a month of this 90-day time limit has passed already so time is running out.

It will not be a straightforward process. Asking Google to change the mechanics of its search engine is akin to reinventing the wheel in technology terms. Failure to comply with the ruling could result in fines amounting to 5% of daily revenue. Google will have to be on its best behaviour for the next five years as it will be under the EU spotlight until 2022.

Additional antitrust penalties may follow, with associated cases relating to the use of Google's Android software and AdSense on-line advertising service ongoing.

EU competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager is likely to probe into the practices of this "dominant company" further, with Google's maps, travel and restaurant reviews all likely to come under her eagle-eyed scrutiny.

Matthew Hall, a lawyer at Brussels firm McGuireWoods, has followed the case with a keen interest. In the immediate aftermath of the ruling, he noted that "all of the businesses closely connected to search must be at risk".

The fallout

If the same reasoning as regards anti-competitive practices is applied to Google's other services and becomes binding, it could fundamentally change the company's business model. At the very least, Google has to significantly reassess how it operates within Europe, and with change comes cost.

The ruling has focused the market's attention on a subtle yet incredibly important distinction between EU and US antitrust standards: the EU is concerned with a monopoly's propensity to stifle competition, whereas the US is focused on consumer detriment and rising prices.

It is this very difference which means that many of Google's competitors will be looking over their shoulders within the EU. , Apple, and all have a propensity to leverage new services off a dominant core product.

Fortune magazine recently drew attention to the EU regulator's concerns around "network effects". This refers to the positive correlation between a service's efficiency and the number of users. In other words, the more people use Google's services, the more effective they get.

An additional red flag for Google is that its business model is not conducive to competition. As Elevation Partner's co-founder Roger McNamee recently noted, Facebook's "monopoly" has been instrumental in the success of WhatsApp and Instagram. The same cannot be said for Google Chrome and Internet Explorer.

The Googles of yesteryear

McNamee referred to Facebook, Amazon and Google as super-monopolies, comparing their dominance to Standard Oil.

The richest man in history presided over Standard Oil's empire over a 100 years ago. At the height of its success in 1890, John D. Rockefeller's company controlled almost 90% of refined oil flows in the US.

However, McNamee emphasised that Standard Oil's control of the market was restricted to one country whereas Google's reach is global.

When people think of diamonds, they tend to think of De Beers. In the middle of the 20th century, it controlled 80% of the global diamond market. As new diamond mines were discovered in Australia, Russia and Canada, De Beers' era of complete supremacy came to an end. Today, the company still has a 40% market share.

Founded in 1602, the United East India Company was essentially the first multi-national corporation. It was almost governmental in nature, capable of waging wars, establishing treaties and coining money. By 1699, the company was the richest private corporation in history.

Other famous historical monopolies include Pan Am Airways and American Telephone and Telegraph (), co-founded by the inventor of the telephone Alexander Graham Bell.

Continuing the communications theme, may still be considered a monopoly in some regards domestically.

Despite being required to provide network access to rivals, BT's Openreach controls and maintains the UK's wholesale broadband infrastructure. This natural monopoly means the company is responsible for providing broadband access for 30 million customers.

Costs versus benefits

Adam Smith is regarded one of the most influential economists in history and laid the foundation for modern economic theory in the 'Wealth of Nations'. Smith's thoughts on monopolies still resonate today, with the general consensus suggesting they are contrary to public interest.

Proponents of Smith also contest that they create more costs than benefits. These costs include less choice, higher prices, restrictions on output and less consumer surplus.

Asymmetric information may be an additional disadvantage. This arises when the monopolist has access to more information than the consumer and exploits this knowledge gap to the customer's detriment.

Conversely, monopolies can also lead to some positive outcomes. Corporations of this size may be able to exploit economies of scale, thus producing items at lower costs and passing on the savings to the customer.

An additional benefit is dynamic efficiency, which is closely associated with market innovation and product enhancement. Companies which dominate their domestic market may also be able to develop a comparative cost advantage, thus penetrating overseas markets and generating export revenues for the national economy.

It is clear that once the 90-day period ends, it is the end of the beginning rather than the beginning of the end. Google will be under constant scrutiny from the EU and every aspect of its business may feel the fallout of this landmark case.

If Google is subject to further fines, the ability to absorb these costs may be the least of its worries. Keeping shareholders happy is a far trickier proposition and more bad news could lead to a revolt.

The mere fact that Google can shrug off this record fine with one quarter's profits highlights an interesting challenge. Implementing fines as a method of discouraging anti-competitive behaviour may prove to be increasingly ineffective when dealing with super-monopolies. Regulatory bodies around the world may be starting to take note.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.