Lessons investors can learn from the credit crunch

24th August 2017 15:03

by Emil Ahmad from interactive investor

Share on

A few events can come to define a decade and shape a generation. The nineties may be associated with the Rodney King verdict and subsequent L.A. riots, Bill Clinton's indiscretions or the launch of the internet.

As the new millennium was ushered in, the noughties are intrinsically linked with 9/11, the Indian Ocean Tsunami or even the launch of Facebook. However, for many, 9 August 2007 could be the day that lives on longest in the memory.

This date has come to be regarded as the first official day of the credit crunch, the beginning of a period of global financial austerity not witnessed since the Great Depression.

On this day, froze three funds due to valuation issues surrounding their mortgage-backed securities exposure. The initial tremors of 9 August rapidly gathered pace and ultimately shook the foundations of the global financial system to its very core.

Having recently 'celebrated' the 10th anniversary of this defining day in modern history, it is important to reflect on the lessons learnt and how the financial world has changed.

A banking comeback?

As Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns taught us in 2008, complacency and greed can lead to disaster. Closer to home, Northern Rock and HBOS were bailed out by the UK government as the global banking sector rapidly realised that its hallowed institutions were no longer "too big to fail".

A complete regulatory overhaul was essential and banks are in a far healthier state today. Leverage was once synonymous with profits but rapidly become a dirty word associated with the worst excesses of banking.

Basel III has forced banks to reassess their capitalisation levels and add equity and convertible debt to their balance sheets.

In considering the 30 most "globally systemically important" banks, the Bank for International Settlements in Basel noted that they had increased their common equity by approximately $1.3 trillion (£1 trillion) between 2011 and mid-2016.

Unsurprisingly, US banks have been leading the pack in this regard as the sector struggles to restore its tattered reputation. Steve Eisman, senior portfolio manager at Neuberger Berman, suggests that this strengthening of core capital ratios corroborates the unlikelihood of another Big Short.

In his recent comments to the press, Eisman stated: "The reality is the system is much safer today and there are not any systemic concerns… Even if (I) were to see a problem with sub-prime auto loans, which some cite as a concern today, there is simply not enough leverage in the system to create a major systemic issue like a decade ago."

Within Europe, the banking picture is slightly less rosy. Ultra-loose monetary policy, elevated levels of non-performing loans (NPLs), Brexit uncertainty and massive fines all serve to highlight the current predicament of the European banking industry.

Lenders are shutting up shop with , , and BNP intending to close operations perceived as less profitable. Recent mergers and consolidations in Spain and Italy have been driven by necessity as the prospect of more bankruptcies loom.

Spanish bank recently agreed to buy Banco Popular for a symbolic price of €1, with the ECB stating that the latter was "failing or likely to fail". 'Bail-ins' of this nature could become ever more prevalent across the Eurozone unless the problems of NPLs and balance sheet structuring are addressed.

This sector consolidation could lead to a higher level of systemic risk across the region. Italy's banks are suffering from the greatest levels of stress, with NPLs of $400 billion approximately triple the EU average.

A disparity of this level means a quick fix is not imminent and Morgan Stanley recently suggested Italy could take "…almost 10 years to reach European NPL levels at the current rundown rate".

An interesting era

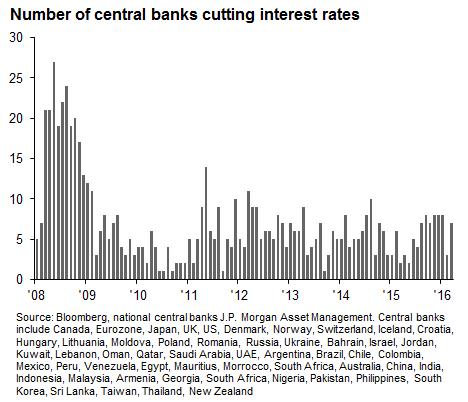

As the financial crisis evolved into the Great Recession, governments were using every tool at their disposal to prop up the ailing global economy. Interest rate cuts quickly became a central bank pandemic as the panic set in.

Figures released by JPMorgan in the fourth quarter of 2016 revealed the full extent of this activity; in essence one rate cut every three trading days since Lehman Brothers' fall from grace.

These top 50 central banks have been responsible for 690 rate cuts since that fateful day in September 2008. This low interest rate environment has persisted for a decade, with a generation of savers suffering from a financial hangover while the borrowers have gone on a spending spree.

Despite a tightening credit cycle which began in December 2015, the Fed's benchmark interest rate still only stands at 1.25%. This is a far cry from its pre-crisis level of 5.25% in August 2007.

In the UK, consumers are still enjoying a historically low rate of 0.25%, as savers sadly reflect on the 5.75% base rate of a decade ago. Europe paints a similar picture, with the benchmark rate of 0% a stark contrast to the 2007 level of 4%.

These historically low interest rates reflect the slow global recovery over the last decade.

Even as global GDP growth has gained a degree of impetus in the last couple of years, incredibly low inflation has helped keep interest rates at subdued levels.

With inflation running well below the Fed's 2% target level, the US is reluctant to enter an aggressive tightening phase and will seek to normalise rates gradually. A recent paper from Federal Reserve researchers Michael Kiley and John Roberts suggests that the new normal will be around 3%.

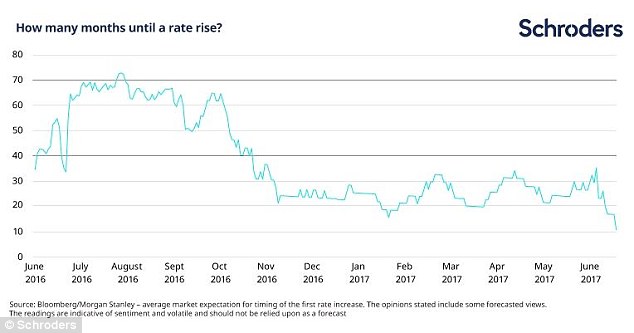

Central banks around the world are looking towards the US for direction and the Bank of England is no exception. As MPC dissenters became increasingly vocal and rhetoric more hawkish, the case for a UK rate rise was growing in June.

Interest rates have once again been kept on hold at 0.25% in August with the Bank talking in terms of higher inflation, reduced spending power and a "sluggish" economy.

Although this could help keep rates on hold until mid-2018, tighter monetary policy is an inevitably rather than a possibility. When this actually materialises, there could be serious ramifications for the debt-laden UK consumer.

Generation credit

The decade following the credit crunch may have adversely affected the saver but it has offered some respite for the ailing consumer. As real wage growth and job opportunities stagnated, access to cheap loans and interest-free credit helped keep many UK households afloat.

However, this has resulted in a nation that is increasingly reliant on credit, a question Aviva indirectly addressed in their recent 'Family Finances Report'. Average household debt now exceeds £17,500, the highest level since Aviva started tracking this figure in 2011.

Unsurprisingly, personal loans and outstanding credit card balances are the biggest contributors. Paul Brencher, MD within the Individual Protection division, is especially concerned about the ramifications for the more marginalised families.

He noted that: "Without a financial back-up, any sudden unexpected expense could put low income families in particular under added pressure."

It is clear that even a quarter-point rise in the base rate could constitute an expense of this nature. Reflecting on the 10th anniversary of the financial crisis last week, former chancellor Lord Darling noted that the increasing levels of consumer debt should "raise alarm bells".

Elaborating on this point, Darling observed: "When interest rates go up, and they will go up, if not this year then certainly next year, and suddenly people find they are going to be paying more in their monthly payments, that's when you need to watch out."

With inflation expected to reach 3% before the end of 2017, purchasing power will be eroded even further.

In conclusion, while lessons have been learnt from the financial crisis, there is clearly more work to be done. Banks may be in significantly better shape than a decade ago. However, recent controversies and fines suggest the sector's tarnished reputation will take a long time to recover.

As stimulus is withdrawn and rates begin to normalise, it is important to tread ever more carefully. Notwithstanding market shocks, it is consumers and households who are amongst the most vulnerable.

As more uncertainly looms in the shape of Brexit, we have never been more acutely aware for the need for caution.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.