Ignore your gut feeling, here's a better way to invest

13th September 2017 17:14

by Danielle Levy from interactive investor

Share on

Selling out of poorly performing investments during a market sell-off is one of the most common mistakes investors make. It may feel like a logical move once fear and panic have set in, but in reality it can prove to be the worst possible time to sell, because you end up crystallising losses at the bottom of the market.

In order to avoid this type of scenario, a new breed of investor is aiming to remove the behavioural biases that lie behind these decisions. The idea is to invest in line with principles supported by robust, repeatable academic studies that are peer-reviewed and underpinned by decades of data. These 'evidence-based investors' typically hold a diversified portfolio of assets for a long time and remain invested through the good times and the bad.

While disciplines such as medicine and engineering are supported by bodies of evidence, Craig Burgess, managing director of EBI Portfolios, suggests this has not historically been the case in investment management.

His company manages evidence-based portfolios on behalf of financial advisers. "For some reason, when we come to investing, gut instinct and great stories seem to prevail in a way they really shouldn't," he says.

Peter Sleep, a senior investment manager at Seven Investment Management, agrees. In contrast, he says, evidence-based investing (EBI) is underpinned by a discipline, which seeks to minimise behavioural biases. "It takes away emotional aspects. We are all emotional people. I have never met an investor who doesn't think they can outperform, when in reality very few of us can because we are guided by our emotions, which make us buy at the top and sell at the bottom," he says.

How to create your own evidence-based portfolio

Firstly, reject the notion that you can outsmart the markets and need to constantly tinker with your investments to boost returns. Indeed, the primary focus is on risk rather than return, so this dictates how the portfolio is set up. That focus on risk is crucial: allocating a client the wrong risk profile could mean they panic and sell as the market falls.

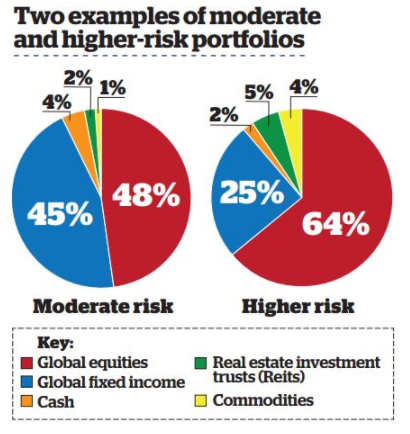

"You have a decision to make at the beginning about what risks you are prepared to take and what volatility you are prepared to have in your portfolio," explains Mark Northway, investment manager at EBI firm Sparrows Capital. "This is about two things: first, your financial position and financial capacity, and secondly, your psyche or psychological make-up."

Each risk profile has an optimum asset allocation based on evidence, and that portfolio has historically produced a certain long-term return, he continues. Investors tend to say: "I need to generate a 5% return", but we say, don't tell us what you expect - we'll tell you what the best portfolio for your risk profile will generate over the long term. If that won't fit your objectives, you'll have to take more risk than you may feel comfortable with, or adjust your expectations.

For each risk profile, target allocations are set for various asset classes and adhered to by rebalancing the portfolio periodically - something known as 'strategic asset allocation'. It hails from the work of academics Roger G. Ibbotson and Paul D. Kaplan, who concluded that strategic asset allocation can explain around 90% of the variability of a fund's returns over time.

Evidence-based investors agree on the importance of establishing the underlying investor's risk profile and capacity for loss at the outset and then reflecting it in the strategic long-term asset allocation. However, the execution of this strategy and preferences for an underlying investment vehicle differ from firm to firm.

Numerous investment-focused academic studies question whether active managers have the skill to consistently add value through their stock selection or market timing. "If the market has made 20% over a given period of time and a fund manager has made 25%, they can be seen as a superb fund manager. But it is very challenging to work out whether it is skill or luck," says Burgess.

Active managers can miss out

Moreover, adds Northway, "active managers tend to de-risk in crises; they are receiving fees to protect clients' wealth, so they tend to take risk off the table when there's a downturn - and then they miss the market recovery."

For 'purist' evidence-based investors the idea is therefore to get rid of the role of skill in portfolio management, making investment an objective process - and then to stay invested as cheaply as possible. Many therefore focus on passive investments such as exchange traded funds (ETFs) and index funds, which take manager skill out of the equation.

Sparrows Capital takes a 'core-satellite' approach, whereby 70-80% of the portfolio is allocated to ETFs and index funds. This provides low-cost efficient exposure to mainstream asset classes such as shares and bonds. The firm advises allocating the remainder to active funds, in order to gain exposure to alternative or specialist investments such as infrastructure, which can be harder to track via passives. "I think the argument about active versus passive has moved on a bit. The question is, what is the role in your portfolio for active and passive?" Northway explains.

Sparrows Capital's next objective is to harvest returns from the market as efficiently as possible. This may involve the use of investment strategies favouring specific factors. "Academics have identified that certain risks tend to get over-rewarded over the long term, relative to others. It is not just that they earn a higher return, but that these risks have a higher risk-reward profile," says Northway.

Thus, studies show that over time smaller companies perform better than large companies. Likewise, unloved businesses that are undergoing change and trade at low price-to-book ratios tend to perform better than higher-rated growth stocks. Academic research also demonstrates that lower volatility stocks have a better risk-reward profile than the market in general.

Another factor is momentum (the process of following the most popular shares as they are buoyed by demand), which investors can gain access to through dedicated funds from Vanguard and iShares.

These factors can also be accessed via 'smart beta' investment strategies, which do not simply follow market cap-weighted indices, but instead introduce certain tilts and biases to track securities that meet particular criteria. Evidence-based investors may look to blend several of these factors.

Andrew Wilson, who is head of the private investment office at Lockhart Capital Management, takes an EBI approach, but is agnostic about whether the underlying funds are active or passive. "We just try to find the most efficient option for any particular market," he comments.

At the current point in the cycle, he says active managers may have the edge over ETFs and index funds in certain markets. "If one assumes we are nearer the end than the start of the bull market, passive is not going to help enormously. Some active managers will also underperform on the way down, but passive definitely won't help you very much," he adds.

Rebalancing the portfolio through a falling market is another strategy that can pay dividends over the long term, because it forces you to buy securities when their valuations are lower - something you may not have been brave enough to do under your own steam.

For investors who are looking to set up their own evidence-based portfolios, there are three options. The first is to do your own research and formulate an approach that is clear, robust and repeatable.

Core to this is understanding what is known as the 'efficient frontier'. This outlines the best possible return you can expect from a portfolio, given the level of risk you are willing to accept; costs will of course be a consideration. You also need to make a decision about the type of fund you are comfortable holding: for example, ETFs, index funds, smart beta or actively managed funds.

Once you are happy with your strategic asset allocation, leave it alone except for periodic rebalancing. To help with this, Wilson suggests creating a rule for how often you rebalance (for instance, annually), and sticking to it.

For those who wish to enlist the help of a professional, the second option is to use an evidence-based multi-asset fund investing in ETFs or index funds, which sets out a strategic asset allocation for you. For example, Vanguard's LifeStrategy funds are baskets of index funds, effectively managed by a computer. Each holds a different proportion of shares, ranging from 20 to 100%, with the remainder in bonds and cash. The funds have an ongoing charge of 0.22%. BlackRock meanwhile offers the LifePath Index fund range.

The third path is to appoint an investment manager or financial adviser who employs an evidence-based approach. This is likely to involve higher costs than option two.

Staying calm when markets tumble is likely to represent the biggest challenge that any evidence-based investor will face. Here, Wilson advises sticking with your process and riding that rollercoaster. "The trick is to not get shaken on a sensible strategy when the going gets tough. Remember you are investing for the long term, and the strategy will look after itself if you can systematically rebalance it and have a good spread of investments," he concludes.

Evidence-based investing - how it can work in practice

Sparrows Capital builds each portfolio according to the client's personal objectives and circumstances. As a starting point, it follows strategic asset allocation models corresponding to each risk profile. It then selects appropriate indices for each asset class, avoiding parts of the market that are less liquid (more difficult to trade).

ETFs are selected based on criteria such as liquidity, assets under management, structure, tracking error (which indicates how closely a portfolio follows the index), cost and sponsor. For factor-based portfolios, the team uses ETFs rather than smart beta funds. They identify factor indices with appropriate methodologies and allocate to these on an equal weight or risk basis.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.