How to spot and avoid consistently awful funds

20th September 2017 17:04

by Kyle Caldwell from interactive investor

Share on

Whether it is in the context of the weekly shop or a car purchase, "value for money" is an idea firmly embedded in consumers' mindsets.

But when it comes to selecting actively managed investment funds, it is impossible to know whether a particular choice will prove to be money well spent, as benchmark-beating performance cannot be guaranteed in advance.

However, there are ways for investors to improve their chances of success, by backing a fund manager who has proved his or her mettle over a couple of market cycles, for example.

But, even then, investors buy hoping for "outperformance", while the reality is that fund management is ultimately a zero-sum game.

Debatable value

Even the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has waded into the debate about the value of managed investment funds. In June, as part of its review into the fund management industry, the City watchdog acknowledged that "asset management products and services are complicated".

It added: "Objectives may not be clear, fees may not be transparent and investors often do not appear to prioritise value for money effectively."

To address these concerns, the FCA has proposed a series of remedies to "strengthen the duty on fund managers to act in the best interests of investors".

One idea that the FCA has begun consulting on is the possibility of increasing the independence of fund governance boards and in turn tasking these individuals with the job of assessing value for money.

However, rather than wait for regulatory pressure to force fund managers to demonstrate their worth, individual investors can use a number of tactics to sort the wheat from the chaff for themselves.

The most obvious starting point is to screen for funds that are perennial underachievers over both the short and long term.

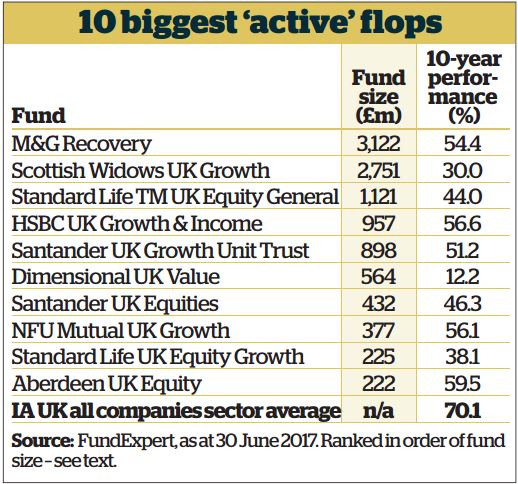

Research by our sister website Money Observer, based on performance figures supplied by FundExpert, looked at the 196 funds in the Investment Association's UK all companies sector that have been around for at least a decade.

We looked at cumulative performance over three, five and 10-year periods to the end of June, and counted the number of funds that produced fourth-quartile performance over each period.

In total, 54 funds, both active and passive, were rooted in the fourth quartile over all three timeframes - some 28%.

But when we adjusted the screen to filter for funds that were in the third or fourth quartile over all periods, the number of underachievers jumped significantly to nearly 60%, with 117 funds failing to break into the second or first quartile over three, five or 10 years.

Serial offenders

The table below lists the 10 biggest fourth-quartile fund performers in order of size.

Billions of pounds are invested in sub-standard active funds. The serial offenders are typically funds run by banks, which tend to be managed conservatively and therefore produce index-like performance, but charge active fees.

Moreover, when it comes to fees, bank funds tend to charge on the high side, with some adopting the fund-of-funds approach, which comes with two layers of charges.

Darius McDermott at Chelsea Financial Services says investment management tends to be a small part of a bank's business and therefore more of an afterthought. "Many have 'index plus' investment strategies. You could look at them as being trackers with a bit extra, or closet trackers," he says.

But picking solely on the banks would be somewhat disingenuous, as familiar fund management names were also among the 46 names stuck in the bottom quartile.

As our table shows, M&G Recovery heads the list of poor performers, followed by Scottish Widows UK Growth and Standard Life TM UK Equity General.

Brian Dennehy, managing director at Fund Expert, says the strategy for investors if an active fund continues to perennially disappoint is "not exactly rocket science". However, although investors can vote with their feet, investor inertia is commonplace.

Dennehy adds: "The fund manager's process must be clear, understandable and repeatable with relative ease, and there needs to be evidence of success over a long period. Anything else is frankly a tad woolly, and underperformance and underachievement are probably a given."

Applying a bit of common sense will help investors avoid funds that should arguably be forced to drop the word "active" from their marketing literature.

The first port of call is to look at a fund's top 10 holdings and compare them with the top 10 constituents in its benchmark index.

A heavy element of overlap - eight names or more being the same - should set off warning bells. Next, chart how the fund has performed against its benchmark index over both the short and the long term.

Adrian Lowcock, communications director at fund manager Architas, says: "If the two lines look similar, the fund is clearly not active enough, as it is failing to deviate from its benchmark one way or the other."

A more scientific and less crude measure is to look at a fund's "active share" percentage. Unfortunately, this figure is not widely available, and fund managers are not required to publish it. However, some fund managers, including Baillie Gifford, have committed to providing the figure in their fund literature.

A fund's active share ratio shows how far its makeup diverges from its benchmark. The higher the figure, the more truly active the fund manager is likely to be. According to McDermott, a figure of 60% or below is a warning that a fund could be a closet tracker. Those scoring more than 85% show "conviction", he adds.

"Picking winners is hard," acknowledges James Norton, an investment planner at Vanguard Asset Management. A recent study by Vanguard highlights the uphill task investors face.

The firm looked at the 548 active funds available to UK investors from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2016. It found that only 237 funds even survived, with the 57% majority either closing down or merging with other funds.

Short of stars

Star fund performers were in short supply, as only 76 of the original funds that survived outperformed their benchmark indices - just 14% of the total. In addition, of the 76 funds that outperformed, 99% underperformed in at least four of the 15 years examined.

"Investors need to ask themselves if they have the patience to ride out what are often long periods of disappointment," says Norton. "As well as being patient, there are two other key ingredients to success when it comes to active funds: a talented manager whose success is down to skill rather than luck, and low fund fees when delivering outperformance."

That said, when it comes to costs, don't make the mistake of thinking passive tracker funds are all as cheap as chips. While the cheapest passive following the can cost as little as 0.1%, some charge 10 times that amount. For example, the Virgin UK Index Tracking fund, which holds £2.8 billion in assets, costs an expensive 1%.

Other behemoth funds that fit the pricey passives description include the £2 billion Halifax UK FTSE All Share Index Tracker (1.03%) and the £1.2 billion Halifax UK FTSE 100 Index Tracking fund (1%). The higher the charge, the more handicapped a tracker is in its efforts to keep pace with the index it blindly follows.

"My concern with costs is that investors often don't realise what they are paying," says Norton. "Fund charges can be intangible, as investors do not pay explicitly, as they would if they buy a car, but through an ongoing charge."

Analysis by Vanguard lays bare the compounding effect of charges over time. A £10,000 lump-sum investment returning 7% a year for 50 years would be worth £295,000 at the end of the period. But when you deduct 2% for charges, the return falls to £110,000.

"In other words, the investor has taken 100% of the risk and has only kept around a third of the return," says Norton. "In contrast, the fund manager has risked none of its capital but kept almost two-thirds of the return."

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.