Why we are selling out of this property focused trust

30th October 2017 09:45

by Ceri Jones from interactive investor

Share on

This month, the concern that stocks will finally shift down from their recent highs has taken root across the market, while at the same time big political events are all but ignored. You can argue, for example, that the separatist referendum in Catalonia is a sideshow because the Spanish stockmarket is small, representing around 5% of the MSCI Europe index, compared with 15% for France and 14% for Germany – but it could have long-term implications in encouraging other areas to vote for independence from the EU, in turn putting the euro under pressure.

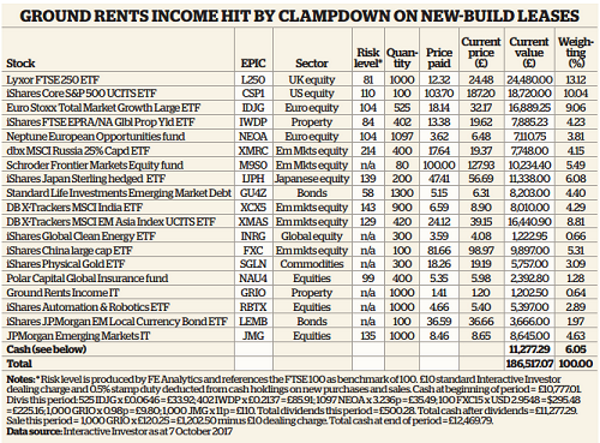

Meanwhile, shares in , our investment in long-dated ground rents, have been hit by the government's consultation on leaseholds on new-build homes. The government is most concerned about leaseholds with ground rent that doubles every ten years in perpetuity, and will still allow flats to be sold on long leases, although ground rents on new leases will be restricted to 'peppercorn'.

GRIO is in fact not seriously affected because only 11% of its ground rent income comes from leasehold houses, and none of its assets have ground rents that double every ten years. Some of the fall in its price is down to panic about a future Corbyn government's hostile attitude to property ownership in general. We bought this REIT because of its exposure to very long-dated and, we thought, reliable rental income. The yield is a steady 3.5 to 4% and remains attractive, at least compared with gilts.

Ultimately, the scarcity of these assets could help the price to recover, but we are selling out now even though the shares already reflect the news, as the future is too opaque for our remit.

Investing globally

The arguments for spreading a portfolio across markets are well-rehearsed. Investing globally removes the UK's high levels of concentration in the financial, consumer goods, and oil & gas sectors; the vagaries of each one over recent years well illustrate the dangers of being overweight in a small number of industries.

Conversely, while the global technology sector has produced some of the most remarkable runaway successes in recent history, the sale of Arm Holdings to Japanese group SoftBank leaves the UK tech cupboard bare. Investors with too much emphasis on the home market are deprived of exposure to this and other dynamic sectors.

Further, concentration is evident in dividend payments: just 20 UK dividend-paying companies account for two-thirds of all dividends paid out by FTSE All-Share constituents. Some of these, notably from and , are not covered by free cash flow; despite attempts by the companies to improve their balance sheets, dividends could be slashed with the same indecent haste as, for example, at .

A broad spread also reduces the impact of any one political event, which may prove important as the Brexit debacle deepens.

On this logic – which is compounded by the likelihood that these regions are most likely to enjoy future growth, and the fact that most developed world stockmarkets are frighteningly overvalued – our Tactical Asset Allocator (TAA) portfolio has long been heavily overweight in emerging markets.

For many years now it has been a nonsense to bunch the so-called emerging economies into one category. In particular, it is flawed to follow a broad index such as the MSCI Emerging Markets index without a good look at its 24 diverse underlying economies. Some $1.6 trillion (£1.2 trillion) tracks this index with a mechanistic approach to mirroring the allocation split, which means, for example, that these funds will hold 15% in South Korea whatever the antics of the North's despot Kim Jong-un.

The distinctions between nations that could be loosely described as emerging are critical, particularly as China matures into a domestically driven economy and the most exciting growth shifts to ASEAN countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, as well as to frontier markets like Brunei, Cambodia and Myanmar.

Shrinking Australia

For less racy but more steady returns, the developed Asia-Pacific economies offer a high income component as well as diversity. The Australian market, which accounts for nearly 60% of the MSCI Developed Pacific ex Japan (Asia-Pac) index, has been primarily driven by China's demand for minerals, and is highly concentrated in resource companies, but service sectors such as education, healthcare and tourism have grown as important exports as the Chinese middle class expands.

On the downside, the stockmarket has shrunk as many foreign firms have bought Australian businesses and removed their Sydney listings, while newcomers have been few and far between.

The MSCI Developed Pacific ex Japan (Asia-Pac) index is 30% Hong Kong, where the banking sector is also growing rapidly, helped by its proximity to China and by initiatives such as StockConnect. Singapore accounts for 11% and is attractively positioned as a gateway to ASEAN economies; moreover, it has undoubted expertise in fintech.

The need to identify the distinctions between regions also holds true in credit: Asia credit is very different from emerging market debt. Far from being a shallow, illiquid market, Asia credit is now a huge and diverse asset class in its own right, supported by strong economic growth with low defaults and good recovery rates, and by improved regulation and standards of governance.

Another reason to make a distinction between emerging and Asian countries is the question of how they might fare in any impending market collapse. The dollar's recent rebound could wreak havoc across emerging markets, impacting governments, banks, the business sector and individual households. All have borrowed trillions of dollars and now face a hike in the real local-currency value of these debts, while rising US rates will push emerging markets' domestic rates higher, further increasing the cost of servicing this debt.

The impact will be softened because the Fed's intention to hike rates this year has been clearly signposted, but the vast amounts of emerging market assets bought by investors in wealthy countries would be sold very quickly indeed, according to quant trading experts who say that any future crash could take seconds rather than minutes or hours.

Investors who want to track these markets could do worse than add a climate change or environmental, social and governance (ESG) screen, such as the MSCI EM ESG Leaders index. Several emerging countries are leading the world in the embrace of digital technologies, fintech and renewable energy, and if the markets do stumble, these are typically sustainable companies with long-term horizons.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.