Would you feel safe in the hands of these investors?

29th March 2018 17:02

head office is round the back of a narrow side street off Borough High Street in London. The door system has broken so a real person lets me in and we tromp up the stairs to a smart, airy, modern office suite acquired at a low rent because the company promised to do it up. Chief financial officer Brad Ormsby tells me the budget was tight. The board table came from Ikea, and as I sink a little too far into my seat, I wonder where the chair came from.

David Cicurel, Judges' founder and chief executive, looks comfortable though, and he's unruffled by my first question, which is more of a statement: That I've put off investigating Judges because it means putting my faith in another investor.

Having faith in another investor

Judges' strategy for the past twelve years has been to buy and build a group of scientific instrument manufacturers.

It seeks out niche businesses, 16 so far, with sustainable profits and cashflows, buys them outright, and operates them. It sounds a bit like management by numbers. Judges agrees annual budgets with its subsidiaries and closely monitors the financials, but it encourages them to be entrepreneurial and doesn't dictate strategy. "If we thought we knew better," Ormsby says, "we'd have a problem".

Order intake, Cicurel says, is the pulse of the business, and cash is critical. The parent treats the cash thrown off by the businesses as its own, investing about 6% of revenue a year in research and development to ensure they remain competitive, and taking the surplus to pay down debt and prepare for the next acquisition.

These investments aren't available to me, and unless you have a very large wallet they're not available to you either. Judges buys private companies at low valuations. So far it hasn't paid more than six times EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Tax, a measure of profit), and it's sometimes paid as little as three times EBIT. To put that into perspective, in the more competitive public market I try and buy shares in good companies at reasonable valuations and its rare today that I find anything below 15 times EBIT. Shares in Judges cost about 16 times my debt and tax adjusted measure of profit, which makes Judges look comparatively good value.

But it's a lot more than Judges paid for the sixteen companies it's now comprised of. The argument for paying a fullish price for past acquisitions is that Judges will go on making investments, and shareholders will continue to benefit from the arbitrage, the difference in value of these companies in private and public markets. "The train is still going," Cicurel says.

Although many of the businesses have grown profits by selling more machines and improving profit margins, much of Judges' growth comes from the deals, the fact that it can borrow money from the bank at relatively low interest rates and buy a company that, crudely speaking, will return 25% of Judges' investment in its first year (assuming Judges pays four times EBIT and this profit is sustained, it will get 25% of its investment back in profit every year).

Profitability roller coaster

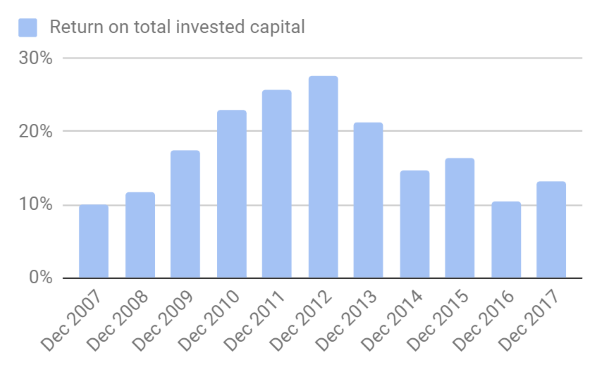

Another thing that has held me back from investigating Judges is this chart, which shows profitability:

In case you're a Judges afficionado and you think my numbers are on the low side compared to similar charts in the company's presentations, they are on the low side. I calculate RoTIC (Return on Total Invested Capital) slightly differently, including head office costs and deducting tax at the standard corporate tax rate. I don't think Judges' method is particularly aggressive, but mine is very conservative so I'll stick with it. The pattern drawn by the bars is the same, and it is the pattern that concerned me.

Most of Judges customers are universities. The company estimates two-thirds of revenue is ultimately provided by government funding, which has been inconsistent since the financial crisis.

That's one reason profitability has fallen since 2012. The other reason is the acquisitions. Judges initial acquisition was relatively expensive, but those that followed were achieved at very low valuations. When Judges buys a company for three times EBIT, it's getting a 33% return on the capital it invested, and although these acquisitions were small, Judges was small, so the combined entity's profitability improved with each new acquisition. Later acquisitions were bigger, and achieved at multiples or five or six times EBIT. Bigger acquisitions had a bigger influence on the combined group's profitability post-acquisition, and higher multiples meant that influence was negative.

I wonder if Judges has gone off big acquisitions. The six it's made in the last two years have been smaller and cheaper, and subsequent digging in the subsidiaries' accounts filed with Companies House reveals Scientifica and Armfield, Judges two biggest acquisitions, made no profit in 2016. Not only did they reduce Judges' profitability because they were big and relatively expensive, they also reduced it because profit was not sustained, at least in that year.

Cicurel says Judges is almost uncontested in the market for companies earning less than £1m EBIT a year, but over that level of profit bigger rivals like Halma and Spectris may show an interest, and so do private equity firms, sometimes with money to burn. The market for larger companies is more competitive, which is why the acquisition price tends to be higher, and it also means Judges is more likely to be outbid, incurring costs but no return.

Limits to growth

I'd come to Judges to find out whether there are limits to Judges growth, and I may have found not so much a limit as a mechanism that could slow growth. The bigger the company becomes, the bigger acquisitions must be if they are to have the same impact on profit, but the evidence so far is bigger acquisition are less profitable. Alternatively, Judges can make lots more small acquisitions, which implies a busy head office that must at some point expand, and perhaps separate into divisions. Ormsby likens the company to a stool with many legs, but there are limits to the number of legs, surely.

With a nod to Halma, a buy and build operation many times Judges' size and still highly profitable, Cicurel thinks Judges has plenty of room for more subsidiaries, although it may have to divisionalise. If it did, it probably wouldn't be on the basis of what its subsidiaries do, as they're pretty eclectic. It's perhaps an indication of how many small scientific companies there are in the UK (2,000 Judges reckons) when Cicurel says it could operate two divisions: Sussex and Hampshire, and that would cover 90% of its operations.

Although Halma wasn't a template for Judges, Cicurel thinks he's improvised a mini-Halma, and the company's latest recruit, chief operating officer Mark Lavelle, previously spent 15 years there.

Judges' strategy also resembles the giant conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway's in its preference for buying companies and largely letting them run themselves. Cicurel is a Berkshire shareholder (he'll be attending the annual meeting this May), but he says it wasn't a model for Judges either, although he admires Buffett's disregard for conventional wisdom.

Reputation, reputation, reputation

Buffett brings me back to another risk on my list. Like Buffett, Cicurel is getting on. He's nearly 70. The company's reputation rests largely on his shoulders, because he's the dealmaker and deals are the primary growth engine. Judges does not mess vendors around. It makes sure the finance is available before offering to buy a business, and does not use the due diligence process to beat the price down. Judges has never welched on a deal because it can't raise the money and it's never had to walk away because it's discovered something nasty. Cicurel says honesty is reciprocated, the vendors are scientists, not "spivs".

One of the reasons Judges can enter negotiations fully funded is it enjoys a good relationship with its bank. On the two occasions Cicurel felt he'd stretched the company's borrowing, to buy two of its biggest acquisitions, the ease with which it restored the company's finances by placing more shares in the market reassured the bankers. Though Cicurel hates diluting shareholders, he's the company's biggest shareholder, needs must.

Cicurel's reassuring on the impact of his retirement. He has no appetite to retire, which he ably demonstrates by offering to go through his sixteen deals one-by one, recounting them in fine detail. I reckon we could have gone into a third hour, but I was flagging by then. Should Cicurel retire, the board has a list of potential successors he believes are ably qualified and suited to maintain the business model. Operationally, the existing businesses would continue as they are. Strategically, Judges board, whose non-executive directors have chalked up too many years to comply with corporate governance standards, would ensure continuity.

I leave Borough High Street impressed by Judges' past, and only moderately concerned about its future. The company says its niche businesses should sustain profits or grow because they make machines that measure and optimise, processes that become more critical and exacting as technology marches on. It supplies higher education, though. I wonder whether we've reached "peak university" funding, but my view could be tainted by a home country-bias that has little relevance to a company that earns 85% of revenue from exports.

I can't see the go-go years before 2012 returning, because government funding of higher education is likely to remain inconsistent. Cicurel says the demand is there, but the money isn't, always. It may also be difficult for Judges to maintain the pace of acquisitive growth given the competitive and organisational challenges ahead. Although Judges has just reported substantial growth in the year to December 2017, aided in part by a return to profitability at the big two, Armfield and Scientifica, and the weak pound, the future may well be more stop-go than go-go.

But I'd feel safe in the hands of these investors. Cicurel says the hardest quality the board will need to replace when he retires is fear, He is "really scared". He feels responsible because so much of his own money is tied up in Judges, and the investments of family, friends and longstanding shareholders like Artemis too. The one thing Judges doesn't need is a hubristic chief executive keen to pull off a massive deal.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

Richard owns shares in Cohort, Dart, Dewhurst, Games Workshop, Science, Solid State, System1 and Victrex.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation, and is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Members of ii staff may hold shares in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Any member of staff intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. We will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, staff involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.

Editor's Picks