"Liquidity trap" management in emerging markets favours trusts

18th November 2014 09:37

by Cherry Reynard from interactive investor

Share on

When Terry Smith, founder of FundSmith, launched his in June this year, he attributed his decision to structure it as an investment trust to fears on liquidity.

He said investors in open-ended emerging market funds could be caught in a "liquidity trap" if there were a run on the asset class. But while some dispute the liquidity problems in emerging markets, there is no doubt investment trusts offer certain structural advantages.

Liquidity has been raised as a problem a number of times in the context of emerging market funds. In 2012, Aberdeen and First State sought to stem flows into their popular emerging market funds so as not to compromise their investment strategy.

Reading between the lines, it was clear that greater inflows would force them into those stocks that offered liquidity - typically the larger, mega-cap holdings - rather than those that were necessarily the best investments.

Liquidity issues

David Reid, manager of the BlackRock Emerging Europe investment trust (BEEP), points out that those running $40-50 billion (£24-30 billion) across their emerging market portfolios - as some of the bigger players do - will always struggle to get money in and out.

That said, this is not a problem confined to emerging markets, but may impact any large fund. Moreover, Hugh Young, managing director of Aberdeen Asset Management Asia, says that liquidity issues may in many cases be little different for developed markets.

"Today liquidity is not an issue of emerging versus developed markets. Some of the world's largest companies are from developing economies. One just needs to look at the size of the Alibaba IPO." Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba Group (BABA) raised a total of $21.8 billion at its launch, making it the biggest US initial public offering ever.

The question is muddied by the fact that liquidity is not static. What looks like buoyant liquidity can rapidly disappear at times of market volatility.

Emily Whiting, client portfolio manager in emerging market equities at JPMorgan Asset Management, says: "When there is a squeeze, [trading] volumes can drop as much as 50%. This is what happened in Nigeria at the start of September.

"That said, larger capitalisation stocks tend to be more resilient. In challenging market conditions, larger blue-chip names tend to become a proxy for the market."

Large cap comfort

"Equally, as emerging markets become more of a mainstream asset class, the liquidity is improving. More companies become investable and grow in size. There are now 1,000 emerging market companies with great liquidity."

But, she adds, smaller emerging market companies or those in less well-developed markets may be vulnerable to bouts of illiquidity. She says: "As you move into smaller companies or 'frontier' markets, it can take days if not weeks to build and sell positions."

This can be a real problem for open-ended funds, which may have to meet investor redemptions during the period, or put investor inflows to work quickly.

It may also impact investment strategy, argues Reid: "There are only two companies in sub-Saharan Africa that trade more than 2.5 million shares per day. This means some managers are forced to look at, say, mining companies listed in developed markets that may have part of their operations in frontier markets.

"This isn't necessarily a bad investment, but it is not great when a fund manager is forced to do it for liquidity reasons."

The MSCI Frontier Markets index covers large and mid-cap stocks across 24 frontier markets, about 127 constituents. The average market capitalisation of those companies is $869.4 million. As a rough guide, this makes them equivalent to the larger stocks in the Alternative Investment Market in the UK.

Bottlenecks

The largest company - the National Bank of Kuwait - has a market capitalisation of $8.8 billion and the total market capitalisation for the index is $110 billion. To put this in context, this is less than a third of the market capitalisation of ($385 billion, as at 18 September 2014). Clearly, in this type of market there will be bottlenecks from time to time.

The majority of fund groups have concluded that this type of investment needs to be structured as a closed-ended fund. Those with longish memories may recall the debacle of the New Star Heart of Africa fund, which was suspended in December 2008.

The open-ended fund could not meet a flurry of redemptions after problems engulfed the management company.

At the time, it blamed difficulties in buying and selling stocks on religious holidays in Nigeria and elections in Ghana, but at its heart was a mismatch between the liquidity it could get from its investments and the liquidity it was offering to its unitholders.

Investment trusts do not get round the problem completely. At times of market dislocation, discounts can move out to extreme levels. The discount on the hit 40% at the worst point in the financial crisis (it is now around 7%).

However, fund groups have gradually got wise to the problem. The was launched with a five-year life span, giving a cash exit at the end of the term. This has kept it trading close to NAV since its launch in 2011.

It currently trades on a small premium. Reid says that this allows the managers the freedom to manage money in the way they want to, free from the constraints of inflows and outflows.

Small markets

Young says: "Closed-ended funds are ideal when investing in small markets, such as Vietnam, or in smaller companies which are less liquid.

"With closed-ended funds, investment managers don't need to worry with daily inflows and outflows - which are often driven by sentiment and occur at just the worst possible times of expensive euphoria or bargain depression - meaning they can truly commit money to companies for the long term."

Many single country funds are structured as investment trusts for this reason. Although some specialist emerging market single country funds - the Baring range, for example - are open-ended, there is a broad range of single country investment trusts, notably those focused on India and Vietnam.

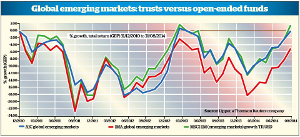

The underlying flexibility can give closed-ended funds a different performance profile from open-ended funds. First, it means fund managers have more room to excel or otherwise. The variation in performance in global emerging market trusts is extreme.

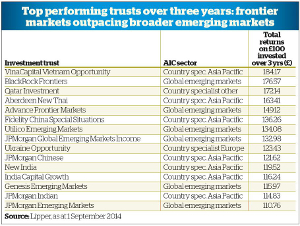

Over three years, the top trust - BlackRock Frontiers - is up 88%, according to data from Financial Express. The worst - the - is down 40.3%. The remaining trusts are spread reasonably evenly between the two points.

The open-ended sector sees less variation. The top fund, is up 39.4%; the bottom, , has dropped 25.7%.

It may also mean that investment trusts are investing in different types of company. Larger-cap companies in emerging markets tend to be dominated by consumer staples, financials, utilities and industrials. These are the companies that float first in a developing economy.

Being able to invest further down the market capitalisation scale introduces the potential for holding new types of company in a portfolio. For example, the holds almost a fifth of its portfolio in technology.

Fastest growth

Reid says: "In emerging markets, the most dynamic, entrepreneurial and fastest-growing companies, and those with the least state influence, are often to be found among the smaller, less liquid names.

"Missing that opportunity set is a massive cost. In our trust, we are not currently positioned in particularly illiquid names, but there are times in the cycle when it is a good idea to do that. The flexibility to do that is important."

It would be wrong to suggest that all the smaller companies-focused emerging market collective investments are structured as investment trusts, and indeed not all smaller companies-focused emerging market funds have suffered liquidity problems during a crisis.

For example, Aberdeen has a £2.23 billion open-ended fund specialising in emerging market smaller companies. The has had an extremely strong five years, in common with other funds with a similar mandate.

It fell painfully during the credit crisis - dropping by around 50% peak to trough - but this was only around 10% more than the wider sector. However, the investment trust structure provides more investment flexibility.

Simon Evan-Cook, multi-asset manager at Premier, concludes: "Ultimately, it depends what the manager is trying to do. If they want to access a wider opportunity set, then a closed-ended structure makes sense.

"If they are trying to access large caps, then it is not a problem. First State has run open-ended funds for decades and never had a problem. That said, a manager in an open-ended fund needs to be aware of the liquidity constraints."

It is not that either investment trusts or open-ended funds are necessarily "better" for investing in emerging markets. But investment trusts offer a different type of emerging markets exposure because they allow managers greater freedom to invest in less liquid stocks.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.