A straightforward money making machine

7th October 2016 17:07

by Richard Beddard from interactive investor

Share on

AGM last month turned out to be my favourite kind of AGM. It was in a small but plush boardroom on the second floor of the company's HQ in Mayfair.

The lift had obviously been battered by rolls of fabric, wallpaper and sample books over the years and, when I queried the small parcel on the floor riding with me in the otherwise empty elevator, reception told me it was supposed to be there.

A fellow shareholder confided he'd got out by mistake on the first floor and wandered around the office. It was very interesting, he said, and suggested I do the same on the way out. Unfortunately, I had a meeting to go to.

Excepting the directors, there were only three shareholders there. David Green. Colefax's biggest shareholder and executive chairman was surprised at the two new faces. It's reassuring when a company is so boring its own shareholders can't be bothered to turn up (although you might query their attitude to stewardship).

Highly respected brands

Colefax designs luxury fabrics and wallpapers and markets them primarily to interior decorators. Its biggest brand, which earns nearly a quarter of revenue, is Colefax & Fowler, which popularised the English Country House style co-developed by John Fowler in the middle of the last century.

It also owns four other brands, some of them more contemporary. One, Cowtan & Tout, is sold exclusively in the US. Such is Colefax's desire to retain their exclusivity, it has resisted the urge to licence its designs for use on products you might find, for example, in John Lewis.

Colefax achieved a 10% return on capital in 2016, marginally below its ten-year average of 11%No doubt the brands, updated each year in new collections, are highly respected by Colefax's very wealthy clientele, but, over the years that Colefax has contributed to the Share Sleuth portfolio, I have wondered about the company's resilience. Return on capital slumped to little more than 5% in 2009 when maybe even lords and oligarchs curbed their budgets.

But with higher stamp duty depressing the market in mansions in the UK, a weak European economy, and Colefax's biggest market, the US, also subdued*, Colefax achieved a 10% return on capital in 2016, marginally below its ten-year average of 11%. Colefax is also that rarity: A company that earns as much in cash, typically, as it does in profit.

People don't write about Colefax much, and it doesn't write about itself much either. This year's Annual Report devoted a whole page to the company's strategy and business model, which is a giant leap forward. The brands have separate design studios, but share other costs like marketing and warehousing.

They appeal to different groups of customers; Jane Churchill is cheaper than Colefax & Fowler, for example. Manuel Canovas is French. This diversification protects Colefax somewhat from ill-winds in particular markets, and also from launching an unpopular collection, perhaps the biggest risk it faces.

Colefax prides itself on its efficient management of stockI'm told it can cost £1.5 million to launch a collection, sample books being the principal cost. Perhaps that explains Colefax's reluctance to develop or acquire more brands.

Fewer brands means fewer products, and less stock. One figure bandied around at the AGM was how few SKUs Colefax stocks. SKU is an acronym for Stock Keeping Unit, in other words each distinct item the company sells. Colefax prides itself on its efficient management of stock.

Stock must be bought from Colefax's 100 or so suppliers, and maintaining unnecessarily large stocks would be a bad idea for at least two reasons. It would require funding, increasing the company's capital requirement and reducing its return on capital.

The company would also have to dispose of more unwanted stock at the end of the season at knock-down prices, also reducing profitability. Apparently, David Green conducts Colefax's end of season sale himself, market trader style, which presumably gives him an annual reminder of the importance of stock control.

Colefax's superpower

Can we validate the idea that Colefax's superpower is stock control? Maybe, by looking at the accounts, or, because it's easier, downloading two line items from SharePad (a popular investment data service).

The efficiency with which a business converts stock into sales is measured by the ratio between stock (aka inventory), which is usually valued at cost, and cost of sales (also known as cost of goods sold, or COGS) in the year.

Cost of sales is the cost of raw materials and labour incurred in production. In Colefax's case it must mostly be the cost of finished fabric and wallpaper as it outsources production.

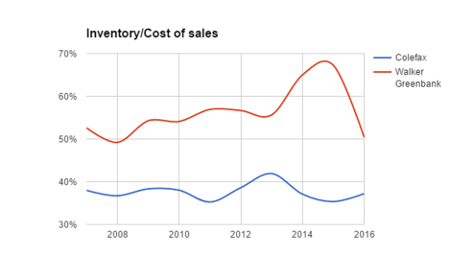

Here I have plotted the statistic for the last ten years, and compared it to , Colefax's listed rival:

The comparison may be unfair, I'm not sure the two companies account for inventory in the same way and Walker Greenbank is different, it manufactures wallpaper and fabric for its own brands and other companies too. But on this one measure Colefax may have an advantage.

While Colefax consistently maintains stock levels at 40% or less of the cost of its annual sales, Walker Greenbank consistently maintains stock levels over 50%. The plunge down towards 50% in 2016 is unlikely to mark a dramatic improvement in Walker Greenbank's stock control. One of its sites flooded last year, destroying the stock.

A money-making machine

Colefax owns famous brands, it keeps them fresh, and it supplies them efficiently. That's enough to earn it returns on capital that are both reasonably attractive and reasonably stable.

It's a straightforward money making machine.

Colefax's conservatism means it hasn't launched or acquired any new brands for a long time, though, and it has no immediate plans to. Instead, for nearly two decades Colefax has used up surplus cash buying back its own shares (the share count has reduced by more than 60% since 1999). This policy probably limits Colefax to a fairly pedestrian rate of profit growth.

A share price of 470p currently values the enterprise at about £47 million or about 14 times adjusted profit. The earnings yield is 7%. Though that's not desperately cheap, I think it's a pretty safe investment.

*For reasons management has yet to put its metaphorical finger on. It may be uncertainty around the US elections. Or it may be because the one part of the US economy that has yet to recover to pre-Credit Crunch levels is Wall Street. Investment bankers are among Colefax's best customers.

One can speculate about the future of the City of London outside of the EU, the effect of any contraction on Colefax's second biggest market, and wonder whether the company, which I suppose benefits from inequality, would find it tougher going if our new Government acts on its promise of a fairer Britain.

I'm on a panel of investors at the next ShareSoc (UK Individual Shareholders Society) Masterclass on 14 October that also includes SharePad analyst Phil Oakley and ISA Millionaire Leon Borras. Phil's going to give a presentation on cash flow statements. Then we're going to talk about our latest, and our worst investments. Lots to talk about, then. For a £10 discount on the ticket price use the code 'beddard' when you register. You'll also get a complimentary six months membership of ShareSoc.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.