Can global economy handle QE withdrawal symptoms?

19th July 2017 12:53

by Emil Ahmad from interactive investor

Share on

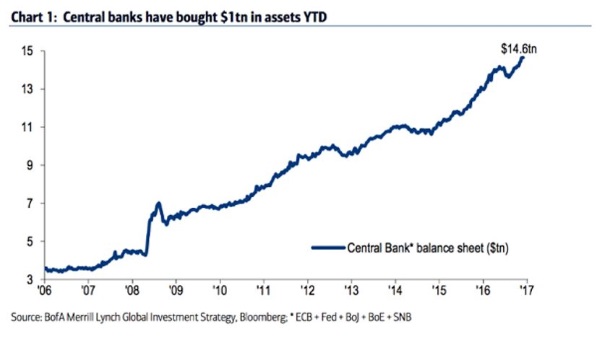

The QE elephant in the room is rapidly becoming a herd. As of April 2017, the balance sheets of the world's major central banks had inflated to a colossal $18 trillion (£13.8 trillion).

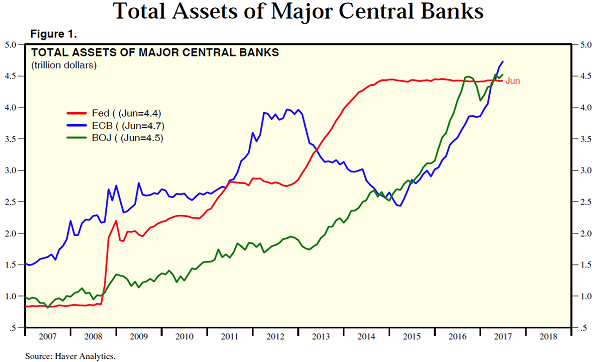

Breaking this figure down does not make it any easier to digest. The People's Bank of China accounts for the largest chunk of change with $4.9 trillion assets held, closely followed by the Bank of Japan ($4.52 trillion) and European Central Bank ($4.44 trillion). The Federal Reserve has a mere $4.43 trillion.

The quick fix that became permanent

Quantitative Easing (QE) has been gathering pace since the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, reaching a stampede at the start of 2017. The $1 trillion of assets bought in the first three and a half months of 2017 represents an annualised figure of $3.6 trillion, the largest total since the QE phenomena began in earnest 10 years ago.

The financial crisis set many precedents and created a whole new set of economic problems which traditional monetary policy was ill-equipped to handle. As global base rates were slashed to prop up ailing economies, the scene was set for the emergence of QE.

Unconventional monetary policy is only considered when interest rates approach zero. With a repurchasing programme typically focusing on bonds, central banks hope to lower interest rates and increase monetary supply, thus providing economic stimulus.

Looking at Europe at the start of 2017, the Financial Times estimated that QE added 1.5% to eurozone growth over 2015-16 and drove core inflation to 0.9% from negligible levels. QE also performed admirably in a damage limitation role, as public debt levels ran amok within EU countries post-2008. In citing Italy as an example, the FT estimated that without the QE effect, public debt would stand 14% higher at 150% of GDP.

QE infinity reassessed

The tide is changing. The US is in the midst of a tightening credit cycle as it seeks to gradually normalise interest rates. The UK will follow eventually, so the QE beast will need to be tamed.

"The ECB [European Central Bank] has told us it definitely wants to taper and the Fed has likewise confirmed it wants to wind its balance sheet down," said BoAML this month. "Other central banks have chimed in. It may not be coordinated but they are all singing from the same hymn book because the world looks better to them."

However, when cheap money and unlimited stimulus becomes the new norm, the thought of life after QE makes markets wince.

Tapering is the gradual reduction of central bank activity to enhance economic growth and has become synonymous with QE. With the Fed actively considering a reversal of QE, policymakers said at their March meeting that this "…would likely be appropriate later this year" and signposted "well in advance".

Despite being non-committal in providing a clear European direction and timeframe, ECB chief Mario Draghi acknowledges that accommodative monetary policy cannot continue indefinitely.

JPMorgan Chase chairman Jamie Dimon admits that the unwinding process is an unparalleled challenge with the potential for unanticipated disruption. Attending a conference in Paris this month, Dimon said, "We've never have had QE like this before, we've never had unwinding like this before." He further recognised the difficulty of quantifying the risk as "…we've never lived with it before."

Central bank prudence

Realistically, the unwinding of QE and a tightening credit cycle must be a very gradual and carefully planned process. Within the EU, sovereign bond spreads could come under pressure and widen if improved growth prospects and reforms are not in place.

Particularly vulnerable countries such as Italy and Spain could be first to feel the pinch. The 2010-13 European crisis showed us that no-one is safe as households, firms and markets all felt the strain of sovereign stress. Although economic indicators are promising, with core inflation rising to 1.1% in June, Draghi has urged the need for prudence in planning the QE exit.

Despite this cautionary approach, he's already talking in terms of deflationary pressures being replaced by reflationary ones. As Bank of America Merrill Lynch noted in a recent strategy insight, Draghi recognises that a failure to ultimately adjust policy simply becomes more stimulatory.

The ECB says rates will only rise once QE ends, a clear indication that the 2% inflation goal is still very much a work in progress. QE is currently scheduled to run until the end of 2017, with respondents to a recent Bloomberg survey expecting tapering until at least mid-2018. An actual reduction in the balance sheet may begin a couple of years later.

After the US taper tantrum of 2013 led to bond outflows and a surge in yields, it is undoubtedly a case of once bitten, twice shy for the Fed. Communication is likely to be constant, but very carefully managed to minimise market shocks.

The Fed understands this brave new world and the need for larger balance sheets. Despite the risk of long-term inflation and market distortions, the Fed's own book will remain large and fail to approach its pre-financial crisis levels of $0.9 trillion. Increased demand for liquidity in the financial sector is just one of several reasons why a new bar has been set.

William Irving at Fidelity thinks unwinding QE will put limited upward pressure on rates. He told the press, "It will be a slow process, and the terminal size of the Fed balance sheet is probably not much smaller than the one we have today."

With one more rate hike likely in 2017, the Fed's Dot Plot suggests the expected path for borrowing costs remains constant. The 'new normal' at the end of 2019 is expected to be 2.9%, with the median forecast pricing in three rate hikes in 2018.

The UK has been bracing itself for an interest rate hike recently, the first in a decade, with higher bond yields suggesting the market has already priced it in. However, each hawkish dawn is seemingly overcome by an MPC dominated by doves.

In an interview last week, external MPC member Ian McCafferty believes the UK should look towards the Fed for direction. As the US put steps in place to wind down its balance sheet, he feels the Bank's £435 billion asset base should be re-assessed sooner rather than later. Although McCafferty was keen to stress that his thoughts were personal opinion only, he reiterated that "…it would be remiss of us not to at least think about it."

Three members voted to raise rates in June and hawkish chief economist Andy Haldane has been rubbing off on Governor Carney of late. However, one of the hawks has since stepped down, and deputy governor Ben Broadbent dampened the fires around a rate rise this week, pointing toward 'imponderables' in the post-Brexit economy.

As Broadbent is viewed as a swing voter on the MPC, this should be enough to keep rates on hold for the time being. But the market will certainly keep a very close eye on the next MPC meeting on 3 August.

All about growth

While it's clear that central banks will want to minimise market disruption in unwinding QE and normalising rates, change will be unsettling. This is especially the case for fixed income investors where reliance on long-term assessments of economic growth, inflation and policy setting is becoming increasingly tricky.

Rising interest rates and harder-to-find cheap money will also put increasingly debt-laden households under strain. Navigating these murky waters, already muddied by Brexit, will present all participants with their own unique set of challenges.

Predictably, investors point to the spike in bond yields and slump in equities following the taper tantrum of 2013. However, there is reason to be optimistic. Benign inflation would allow gradual withdrawal of stimulus this time and support economic growth, which in turn drives corporate earnings.

Remember, too, that in 2013 the Fed still eventually ended QE, bond yields fell and equities rallied, underpinned by growth and rising profits. According to BoAML, "investors should buy any pullback in equity markets with stabilising bond yields the likely necessary pre-condition for a renewed rally".

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.