A decade on from the financial crisis: Best and worst shares, funds and trusts

15th September 2017 16:06

by Kyle Caldwell from interactive investor

Share on

Ten years ago marked the start of the Credit Crunch, precursor to the denouement of the full blown global financial crisis.

The warning signs, with the benefit of hindsight, were apparent, and they have now been chronicled in the history books; hundreds of thousands of words, in fact, have been written about the period.

Even Hollywood has got in on the act: its take on Michael Lewis's book The Big Short, released in 2015, made a cool $133 million at box offices worldwide.

Somewhat ironically, this figure is close to the sum earned personally by the film's principal protagonist, Michael Burry, when he correctly predicted that the large sums of money flowing into the US residential property market and rising levels of household debt against a backdrop of loose bank lending would ultimately prove unsustainable.

For some, the credit crisis started when French bank BNP Paribas froze three of its funds in August 2007, citing "the complete evaporation of liquidity" due to problems in the US sub-prime mortgage sector.

But for many others, the run on Northern Rock and the queues at the 'holes in the wall' that followed in September that year marked the point at which the credit crunch kicked off.

The former bank was far from alone in receiving help from the taxpayer when the government eventually stepped in to bail out the banks in 2008.

Meanwhile, others, including HBOS, Bradford & Bingley and Icesave, were forced into takeovers or simply went bust.

The FTSE 100 did not start its slalom-like descent until nine months later, when the global financial crisis began in earnest, pushing western economies into painful recessions (the UK economy endured five quarters of negative growth).

In mid-May 2008, for example, the FTSE 100 hovered above 6,200 before falling to 5,000 by mid-September, when Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy sent shockwaves across the globe.

By March 2009 the FTSE 100 had collapsed to 3,500, and this level marked the trough. Peak to trough, the index fell by 44% in the course of a convulsive 10 months, during which various fund sectors slipped into the red - most notably those with a UK focus.

Historic buying opportunity

But 10 years on, given what has followed, it's clear that those steep falls created one of the best ever buying opportunities.

Number-crunching by Money Observer shows that the subsequent eight-year bull market has been a rising tide for every single Investment Association (IA) fund sector.

The biggest winners have been specialist technology funds, followed by the North American smaller companies sector, up 227% and 209% respectively from 13 September 2007 (the day before Northern Rock asked the Bank of England for emergency funding) to the end of July this year.

Following closely behind are the Japanese Smaller Companies sector, up 183%, and North America, up 168%.

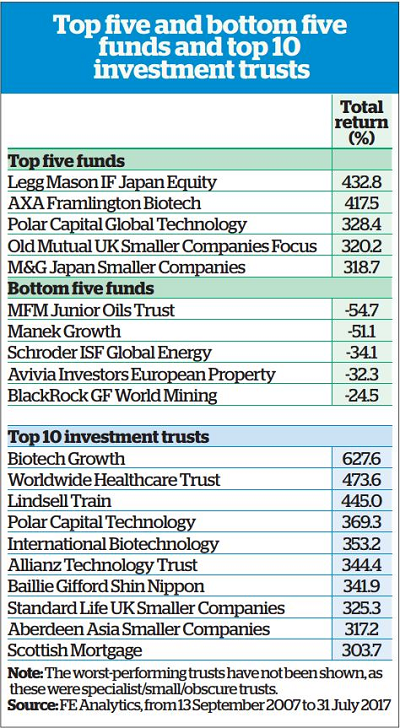

In terms of individual funds, the top performers for funds and investment trusts are shown in the table below. Japan - and biotech-focused funds feature among the winners, but for completely different reasons.

Biotech has boomed because of favourable supply and demand dynamics; huge advances are needed to provide drugs and treatments for the world's ageing populations. Japan, on the other hand, has benefited from ambitious political reforms. Share prices have been further helped along by quantitative easing - a controversial monetary policy that has also benefited markets in the UK, Europe and the US.

Joe Le Jéhan, a multi-manager at Schroders, explains: "Low interest rates and the effect of money being pumped into the economy have benefited businesses and therefore the stockmarkets on which they are listed. Low interest rates have enabled companies to restructure their balance sheets at lower cost because loans are cheap."

Smaller versus large

Smaller companies funds in general have shone more than their larger peers: for instance, the sector average return over the near-10-year period for the European smaller companies sector stands at 142%, well ahead of the European ex UK sector average return of 91%.

In the UK a similar pattern has played out, with the UK smaller companies sector average standing at 133%, compared with 79% for the UK all companies sector.

For seasoned investors, including Richard Power, manager of the , this does not come as a surprise.

He says: "During the crisis I had to put my trust in the underlying performance of the businesses I invested in and then patiently wait for share prices to recover in due course. Smaller companies have more scope to grow than larger names (such as those listed on the FTSE 100) and over the long term tend to outperform. The trouble is, most investors only consider investing in smaller companies after they've seen a sustained recovery take place."

Certainly, figures from the IA show that investors have generally given smaller companies-focused funds the cold shoulder over the past decade.

Since September 2007, net retail sales have been in positive territory in just four years.

Bonds, on the other hand, have been in vogue. The two standout years were 2009 and 2011: over both years the corporate bond sector was the bestselling sector with retail investors.

Overall, despite the significantly higher returns available on equity markets, bond investors who adopted a buy-and-hold mentality over the past decade won't be complaining, with the average fund in the sterling corporate bond sector up 66%.

That's not a million miles away from the IA UK all companies sector average return of 79%, as shown in the asset class performance chart (see box above).

As one would perhaps expect, the riskiest bond area, high-yield bonds, beat most other fixed-income sectors, returning 77%. But taking top spot was the arguably even riskier, global emerging market bonds sector, which delivered a return of 114%.

Tom Stevenson, investment director for personal investing at Fidelity International, adds: "Bonds have benefited from the collapse in interest rates in the wake of the financial crisis, but without first suffering the savage bear market that equities experienced in 2008 and the start of 2009."

Some losers

Not everyone has been a winner, though. Those who sought refuge in cash during the crisis and remained on the sidelines during the subsequent recovery will have seen the value of their money fall in real terms, due to the effect of inflation.

Since the crisis, savings rates have plummeted, particularly after interest rates were cut to a then historic low of 0.5% in March 2009. Prior to the crisis some cash ISAs were offering interest rates of 6%, but today savers are lucky to find banks or building societies offering rates higher than 1%.

This, however, has not been enough to end the British public's love affair with cash. Eight in 10 ISA investors opted for cash ISAs in the 2015/16 tax year. In contrast, ISA flows into funds have only been positive in three years -2009, 2010 and 2011 - according to the IA.

On the whole, caution has not paid off. Other low-risk areas have failed to shine since the crisis. The targeted absolute return sector is up just 31%, while the two most conservative multi-asset fund sectors - mixed investment 0-35% shares and mixed investment 20-60% shares - have also lagged, up 44% and 52% respectively.

However, this is arguably in line with how investors should expect these funds to perform.

The biggest losers were investors who bought specialist commodity funds a decade ago and then failed to sell them ahead of the savage bear market that crippled the sector from 2011 to 2016. The worst fund performer since the credit crunch, MFM Junior Oils Trust, declined by 54.7%.

Whether you are a winner or loser also depends on whether you were investing for the future or living off your investments during the crisis.

"For investors in accumulation, risk assets have been the right place to be," notes Anthony Gillham, who runs various multi-asset funds for Old Mutual.

"But what is less talked about is the devastating compounding effect that bear markets have on investors in drawdown who are relying on income from the stockmarket to support their lifestyle in retirement - those in this camp are among the big losers."

Striking the right balance has paid off

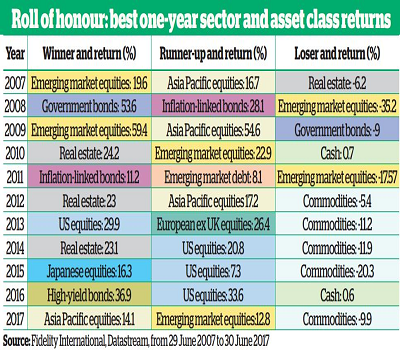

Market timing is often described as a fool's errand, and taking a quick glance at the accompanying table, you can see why. Since the crisis, a winning asset class or sector one year has tended to disappoint the next.

Overall, however, investors who stayed the course will have seen the value of their investments go up, particularly those who spread their bets across various sectors and asset classes. According to Fidelity's Tom Stevenson, one of the biggest investment lessons of the past decade has been the benefit of a balanced portfolio.

He adds: "While there have been some years when every single asset class has risen, and some when there was a mixture of risers and fallers, there hasn't been a single year in which everything has fallen together.

"This is really good news for a hands-off, long-term investor, because it shows that diversification works. It's a compelling case for putting together a well-balanced portfolio and simply holding it for the long term."

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

This article was originally published in our sister magazine Money Observer, which ceased publication in August 2020.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.